Agnese Bartolucci: ‘I care deeply about understanding social phenomena’. Information design and the role of a data scientist

What is information design, and what does it mean to you?

Information design is a multidisciplinary practice that organizes and presents complex information clearly, accessibly, and effectively for a specific audience, with the aim of helping them complete a task or understand a concept. It draws from many fields: graphic design, for visual communication and style; communication design, for effective messaging; user experience (UX), to understand how people interact with information; instructional design, for structuring information to facilitate learning; and, perhaps most importantly for me, data visualization, which presents complex data through charts, graphs, and other visual forms.

I tend to define myself by many words: as an information and data visualization designer, because visualization is often the primary design output I focus on; and also as a researcher, since I am equally involved in collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data. This combination makes me, in a sense, a data worker—someone who knows how to do many things with data.

Information design, to me, is a beautiful and important discipline.

I enjoy, and take pride in, helping others understand complex concepts by making them clearer through visualization. For a long time, I also described what I do as “making data beautiful,” and I still hope my work feels that way.

However, as Akbaba reminded me in her talk at Visualizing Knowledge 2025, complexity itself often carries an aesthetic dimension. The problem is that this aesthetic is frequently associated with minimalism, which has been elevated as a universal standard but is actually rooted in specific cultural values.

This is why I approach both information design and data work with as critical an eye as I can. I am an overthinker, but in this field, that is a resource: always asking why I am doing something in a particular way, who my influences are, and how I might be more mindful and inclusive of different perspectives. Coming from a design school where precise trends drove aesthetics, I found Data Feminism by D’Ignazio and Klein (2020) to be an eye-opening read. Feminism, and especially intersectionality, is the foundation of my practice as a data worker, where I strive to modify processes—albeit slightly—so that they better reflect the experiences of minorities, the complexities of human life, and the realities of discrimination.

An information designer is a true multiskilled research team member. Tell a story about how, in practice, a good collaboration looks like and your interests in analysing important social processes.

Good collaboration with an information designer depends on their skills and interests. As a designer and researcher, I can often handle much of the process, resulting in data visualizations in fields and with methods I am comfortable with. In my professional experience, the most interesting collaborations were with clients who had a large amount of data, a sense of what story they wanted to tell, and no clear idea of how to represent it. As an information designer, it is always exciting to be given a cryptic-looking dataset and a blank page, and even more so when the client is passionate about the subject. That passion makes it essential to consider not just accuracy but also the mood of the visualization: for instance, you would not depict data about cruelty to animals with cheerful cartoon puppies.

In Menopausing, collaboration will mean translating between disciplines. I look forward to learning from my colleagues, seeing how their data aligns with mine, and helping structure it into visual maps that highlight themes, relationships, and silences. I also look forward to gaining a deeper understanding of the societal context surrounding the menopause through the expertise of my colleagues, so that I can analyze and interpret my data more precisely.

I care deeply about understanding social phenomena, especially when they disproportionately affect women. As a woman, I am aware of how often the responsibility to address our issues—whether related to health, work, or care—falls on us, while being systematically ignored and underfunded. For my master’s thesis, I studied gendered violence in digital spaces, specifically image-based sexual abuse (commonly referred to as revenge porn). The research was painful and often disheartening, since I examined the online communities where this violence was carried out, with their dehumanizing language and practices. Yet it left me with an understanding of digital dialogue, a familiarity with digital methods (Rogers, 2013), and a strong sense of the importance of studying and discussing such issues. That urgency drives me again now, as I turn to menopause as another underexplored social issue that can be explored through digital spaces.

How do you think your study environment will shape your contribution to Menopausing? Can you give some examples?

My academic path has been design-focused from the beginning, with both my bachelor’s and master’s degrees in design. That made me first a designer and then, gradually, a researcher. I owe much of my interest in data and visualization, as well as in research more broadly, to the DensityDesign Lab, where I first encountered the discipline in practice. Through my master’s thesis, I experimented with digital methods and working with data across the full cycle of collection, analysis, and visualization. That experience laid the foundation for my research approach and will significantly shape my contribution to Menopausing.

My environment at Aalto is taking care of the rest. I am here as a PhD researcher, reimagining digital archives through intersectional feminism, asking how design decisions around interface and categorisation can make collections more inclusive. This feminist and critical approach is what I bring into Menopausing, along with a clearer sense of what research actually is and entails (for example, finally beginning to understand what “methodology” means, or what on earth “epistemology” is supposed to be). The environment at Aalto is thriving, and no longer being a “student” in the traditional sense makes me more receptive to different stimuli and interests that were previously overshadowed by project deadlines and grades. Being surrounded by such a diverse and varied community of designers and artists is enriching, and I believe it will make me far more adaptable and open to the uncertainties and hidden possibilities that come with approaching this project. Ultimately, what I’d love is to create a connection between my doctoral research and Menopausing, since both are equally concerned with whose experiences are archived, how they circulate, and how design mediates them.

Can you give a sneak-peek insight from your initial attention to digital landscapes, discussing menopause?

Even as a simple user, I am always entertained by the diverse ways in which social platforms are utilized. This comes naturally, since their affordances are intentionally designed to encourage specific actions. As Philips and Milner (2017) put it, “you can’t, for example, very easily use a child’s car seat to mail in your taxes or burn down your house.” What a digital platform allows, and sometimes prompts you to do, is fascinating.

For menopause, the contrast between Instagram and Reddit is especially striking.

On Instagram, most people used to publish a polished version of their lives, until some discovered its potential for activism and information-sharing. Here, non-anonymous and often personal accounts—sometimes reaching large audiences—share visually appealing resources, initiatives, and personal experiences. By design, Instagram privileges creators who can combine aesthetics with clear messaging.

Reddit, on the other hand, is structured around community and anonymity—look at the usernames, it is almost impossible to find someone’s real name! Menopause is divided into subreddits, where anyone can post if they follow the rules, ask for advice, or share experiences that others can comment on and enrich. Unlike Instagram, Reddit doesn’t naturally support famous content creators; it is, at its core, a peer-to-peer space, for better or for worse.

It was therefore natural for me to choose these two platforms as starting points. On Instagram, I will focus on content creators—activists, politicians, healthcare professionals—who have built communities of followers around menopause and ageing. On Reddit, I will focus on the plural rather than the singular, exploring communities where people seek help, resources, sympathy, and solutions.

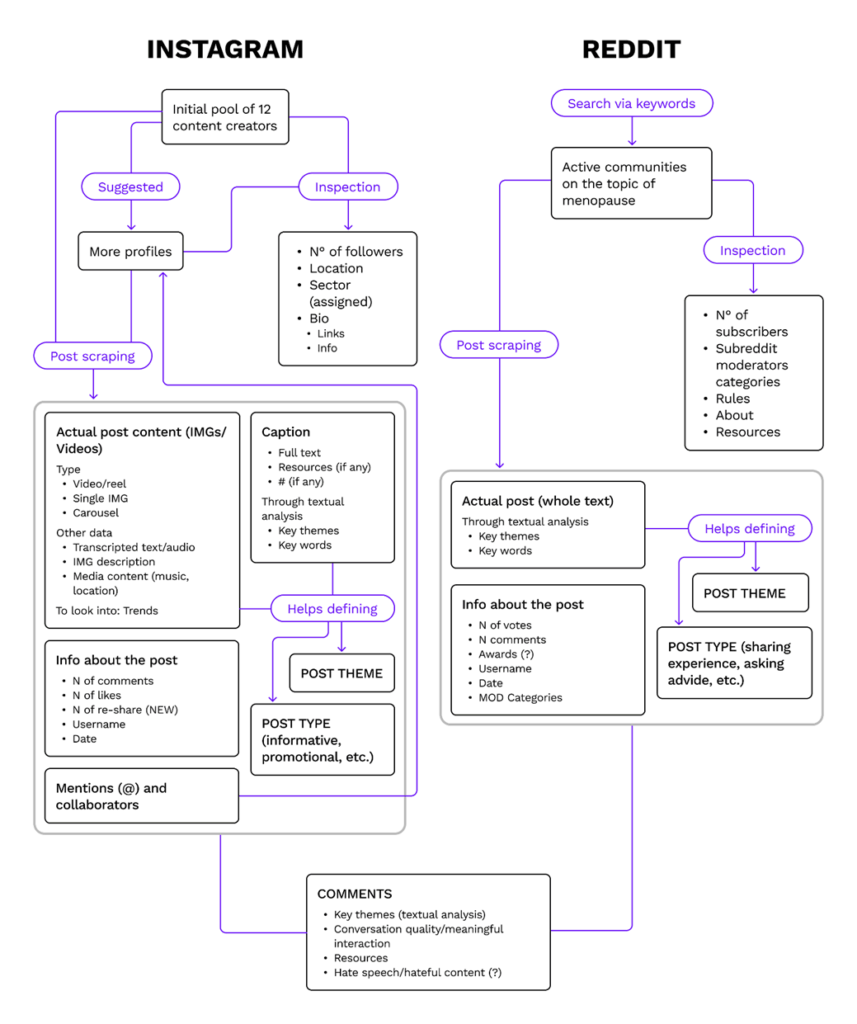

Different platforms call for different types of collectible information, and this is how I am currently hypothesizing the structure of my research. The diagram below outlines how I might connect posts, comments, advice, and resources across Instagram and Reddit. At this stage, I am expanding the pool of Instagram profiles to map them geographically, establishing a first set of subreddits, and beginning data collection on posts and threads.

What I am most excited about, and what I hope will be my most meaningful contribution, is the textual analysis of both Instagram and Reddit content. First, I want to analyze the posts themselves to identify key themes and keywords, which reveal the kinds of topics people choose to raise, emphasize, or revisit. Alongside this, I am also planning (though still deciding on the best approach) to collect and analyze the comments associated with each post or thread.

Comments add another layer: they reveal not just what is being discussed, but also how people respond, the resources they share, and the overall quality of the conversation.

In short, I aim to identify both the topics that generate the most meaningful interactions and how communities actively assist one another in navigating challenges that many mainstream healthcare institutions continue to overlook.

For me, this is about tracing how folk knowledge circulates online, driven by mutual care and kindness. Of course, I would be thrilled to expand this study beyond Western-centric platforms. I am still grappling with how to overcome my language barriers and move outside my Western social media bubble, but it is crucial. While menopause affects only those who menstruate, it intersects with different and often marginalized identities in very different ways. The strategies and forms of care that emerge in those contexts may look radically different from the ones I encounter in Western communities, and that makes them equally worth studying.

***

Cite: Bartolucci, A. (2025) ‘I care deeply about understanding social phenomena’. Information design and the role of a data scientist, interviewed by A. Lulle, 7th Oct.

Resources

- Agnese Bartolucci’s website

- Agnese Bartolucci’s profile in here, Menopausing website

- Derya Akbaba’s website

- Conference “Visualizing Knowledge 2025 – Visualizing Resilience”

- “Data Feminism” (2020) by Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein

- MIT Press Direct – book “Digital Methods” (2013) by Richard Rogers

- Research lab “DensityDesign Lab”

- Aalto University

- Wiley – book “The Ambivalent Internet: Mischief, Oddity, and Antagonism Online” (2017) by Whitney Phillips and Ryan M. Milner

- Interviewer Aija Lulle