Elena Ppali: Patient-Oriented research: Is it really necessary?

Due to the ‘Publish or perish’ mindset dominating today’s scientific community, scientists, including the ones in the field of health and disease, often focus all their attention and resources in generating data and publishing papers, completely losing sight of why they got into their field of research in the first place – to revolutionize how patients are being diagnosed and treated.

Consequently, the further research moves away from patients, the need for more patient-oriented approaches to research becomes more evident.

It should also be noted that failure to translate scientific findings into successful clinical trials is perhaps one of the biggest obstacles in drug development. Could it be possible that the inability of scientists to fully grasp the impact a disease has on the patient and their loved ones is contributing to this failure?

Undoubtedly, the amount of details regarding the specific molecular mechanisms that scientists can share far exceeds anything that a patient without a research background could ever tell you about their disease.

But do scientists have experience with the disease outside of the lab? Are they themselves, or a loved one suffering from the disease they are studying? A lot of the time, the answer is no. Take me for instance; I am studying the molecular mechanisms of Frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, but I don’t have either of those diseases and neither do any of my loved ones.

Unfortunately, because of the absence of lived experience and the pressure to continuously publish results, researcher’s priorities and goals often differ from those of the patient, and sometimes even those of healthcare professionals. So how do we know what is actually important to the patient if we don’t ask them firsthand? How do we avoid scientific results with no clinical applications?

Patient-Oriented Research (POR): A Paradigm Shift

Reading my previous blog post, where I described my research, as part of the Neuro-Innovation PhD programme, you will notice that a small – but important – part of my project focuses on patient engagement. We decided to include this part as a way to ensure that the project becomes more patient-oriented rather than solely focusing on lab results.

Admittedly, at the start of my scientific career, when all my energy was spent on generating enough data to write my thesis, I would have questioned whether including a patient engagement part in my research was really necessary. Working in the lab is already extremely time-consuming on its own, why would I take on more responsibilities? Is patient engagement in lab work even that important?

Today, although still actively trying to avoid failed experiments and generate as much data as possible, my answer to that last question is a resounding yes. A patient’s unique insights into disease are necessary to bridge the gap between scientific results and clinical applications. And as evidenced by the various initiatives encouraging patient engagement in research and the growing demand for patient engagement by funding bodies, this is an opinion I share with many members within the scientific community.

Thus, an alternative type of research, referred to as patient-oriented research (POR), is becoming increasingly popular among scientists.

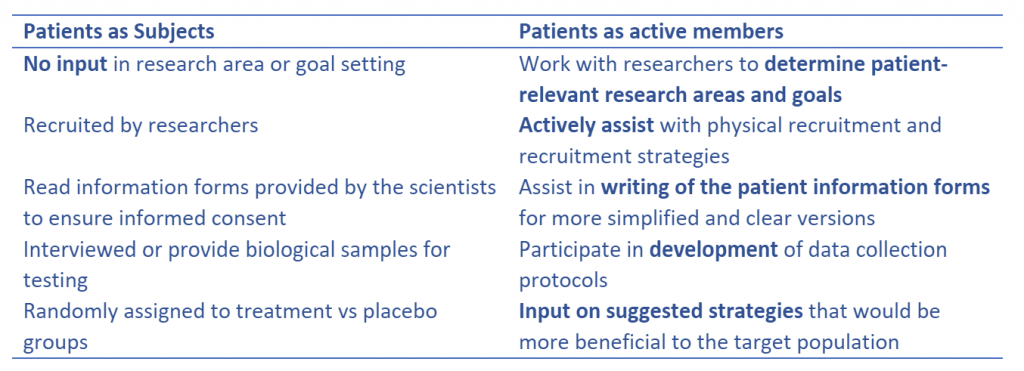

In a nutshell, POR is carried out with the patients rather than for the patients. Patients move away from their traditional role as research subjects and become integrated in the study as active team members. They form meaningful collaborations with researchers and contribute throughout the different stages of a research project.

The table below, adapted from the Faculty of Medicine at the University of British Columbia, perfectly summarizes how patients shift from research subjects into a more active role.

By engaging with patients more, scientists have the chance to view their research through the eyes of individuals with lived experience with the disease, either as a patient, a family member, or a caretaker. This gained new perspective can go a long way in improving the applicability of research outcomes in the clinic.

The inclusion of patients in research, from start to finish, also ensures that patient-identified goals are set from the initial stages and that the whole process is moving towards patient-relevant outcomes. Additionally, POR can be a very important tool for finding middle ground between the priorities of the different parties involved, since it leaves more room for open and honest discussions regarding the different expectations of researchers and patients.

Challenges in Embracing POR

However, nothing good comes without its challenges. Because POR is a relatively new concept, the tools available for actively recruiting patients are very limited and there is a general lack of guidance on how to successfully incorporate patients as research partners.

The need for additional training, for both patients and scientists, also increases the time and costs of the study. On one hand, to effectively contribute to the research, patients need to receive the proper training to gain a deeper understanding of the entire process. On the other hand, scientists need to learn how to engage with patients and how patients can be included in the research for maximal benefit.

This adds another layer of complexity that discourages scientists away from POR. Moreover, because of the lack of appropriate frameworks for assessing its effectiveness, the impact of POR becomes difficult to measure, making it harder to determine any long-term benefits. This can make scientists hesitant to turn towards POR. Who would want to carry out research that will cost them more money but has no proven benefits?

At the end of the day, whether and how POR is incorporated into a research study depends on the scientist. Different scientists share different opinions. Some scientists argue that the limitations that come with patient-oriented research are greater than its benefits. Actively including patients in a project becomes more time and money consuming, without convincing evidence of a more significant impact on the actual results or increased applicability in clinical trials.

Others believe that patients, as the end-users of any drugs or diagnostic tests developed, have the right to be more involved in something that will impact their quality of life.

I personally think that as scientists, we should start making more effort to actively involve patients in our research as they are the ones affected by any novel findings.

Additionally, any new insight we get about a specific disease, no matter how insignificant we think it is, could be the key to treating or even preventing the disease. POR has the potential to transform how research results are being translated into the clinic, but until it becomes more widely used, we will never see its benefits.

Elena Ppali works as a doctoral researcher in the Neuro-Innovation programme. She studies a new gene mutation that increases the risk of Frontotemporal Dementia and Alzheimer’s.