Elena Ppali: We need to talk about dementia

Once people learn that I am a PhD researcher in Finland, the first question I get asked is whether I have seen the Northern Lights – I have, twice – followed by a question about what my research is about. My default answer to the latter is always something along the lines ‘I study a specific gene mutation that increases the risk of dementia’. Now, this is an oversimplified answer barely touching on what I actually do. Regardless, in my experience, this is the best way to go – anyone that is interested to learn more will ask, and any more detail will just confuse anyone that has limited or no knowledge of complex biological processes and Neuroscience.

The only caveat with this answer is that I am generalizing dementia into a single entity, leaning into existing misconceptions around this condition. The minute people hear the word dementia, many assume that I am studying Alzheimer’s disease, and although they are not wrong – a part of my project is specific to Alzheimer’s disease – this is not the only type of dementia that exists, and it is not the primary type of dementia my research focuses on. So, what does the term dementia refer to?

What is dementia, and what are the symptoms?

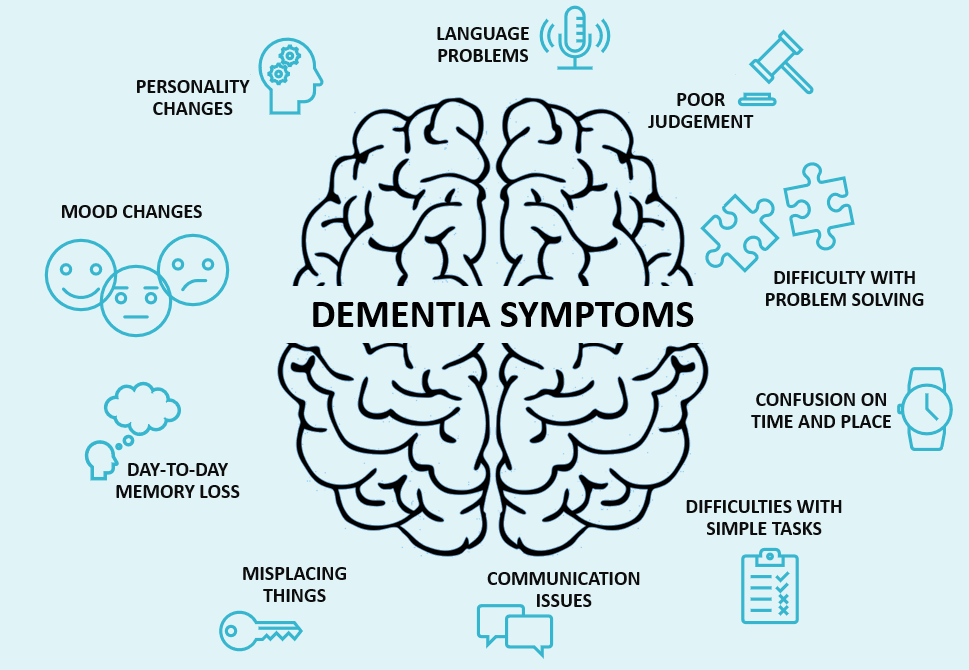

Dementia is not one specific disease, instead it is an overarching term describing a group of diseases characterized by progressive cognitive decline, associated with degeneration of brain matter. Although symptoms are diverse and the disease manifests differently from individual to individual, even if they have the same diagnosis, there are some common symptoms in the early stages that people should look out for, summarized in the figure below.

On more than one occasion, I have heard people use dementia and memory loss interchangeably – someone with memory problems surely has dementia, especially if they are above a certain age. However, so many factors can affect your memory: stress, lack of sleep, ageing, certain medications, even depression. Dementia on the other hand, is much more than memory loss. It affects how a person thinks, behaves, speaks or even feels, and it becomes disruptive for everyday life. It should also be noted that, while it is perfectly normal for people to show some cognitive decline as they get older, dementia is not a natural consequence of getting old, and many young people also suffer from some type of dementia.

There are different types of dementia

Here, I will very briefly describe the five most common forms of dementia, although this list is not exhaustive.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia, accounting for 70% of all dementia cases, and probably the most widely known since this is the disease people usually associated with the term ‘dementia’. Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by deposits of certain proteins in the brain that eventually lead to neuronal cell death and shrinking of the brain. Symptoms start with memory loss and difficulty retaining new information and in advanced stages, being disoriented and mood and behavioural changes may occur.

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) refers to a group of diseases characterized by prominent loss of neuronal cells in the frontal and temporal lobes. Because these areas are the ones associated with personality, language and behaviour, FTD presents as behavioural and language disorders and is thus diagnosed as two main distinct subtypes: behavioural FTD and primary progressive aphasia, where language comprehension and speech skills are gradually lost. It should be noted that other rare subtypes also exist. As an early onset form of dementia, FTD tends to begin around ages 40 to 65 years old.

Lewy body dementia is one of the most common types of dementia caused by the buildup of Lewy body protein in the nerve cells. Because of this, this type of dementia starts slowly and gradually worsens over several years and it is rare in people under the age of 65 years old. Damage is usually seen in brain areas associated with thinking, memory and movement. Because one of its earliest symptoms is visual hallucinations, in its early stages, Lewy body dementia is confused with other psychiatric disorders.

Vascular dementia, as the name suggests, is caused by damage to vessels responsible for the brain’s blood supply. Usually, vascular dementia follows a stroke incident, where the brain’s circulation is cut off for a significant amount of time, or it is brought about by narrowed brain blood vessels for a prolonged period. Like FTD, memory loss is not the primary symptom, as vascular dementia usually presents itself as slowed thinking, inability to focus and trouble with problem-solving. Memory loss may appear as a symptom in later stages, but it is usually not as prominent.

Mixed Dementia is used when an individual is diagnosed with two or more types of dementia. For example, someone might be simultaneously affected by Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia.

In addition to these five common types of dementia summarized above, other dementias are also present in the populations. These include; Parkinson’s disease dementia, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome and Huntigton’s disease dementia.

Why do we really need to talk about dementia?

Even though every three seconds someone develops dementia, there is still a lot of stigma and a lack of awareness surrounding this condition, which more often than not delays diagnosis and access to effective treatment. Understanding the different types of dementia is necessary for providing the best possible care to the patients, caretakers and loved ones, through early and accurate diagnosis, access to the necessary treatments and a strong support system. A good start to better educate people is to have difficult but honest discussions about dementia, which will help destigmatize a condition that is affecting millions of people worldwide. empowering patients and caregivers to seek help a lot sooner.

So, if you only take one thing from this blog post, I hope it is that we really do need to talk about dementia.

Elena Ppali works as a doctoral researcher in the Neuro-Innovation programme. She studies a new gene mutation that increases the risk of Frontotemporal Dementia and Alzheimer’s.