Melina Estela Dalmau: Be fair, take FAIRway

Let’s enter a library. That fantasy of several floors full of books, comics and music. Even 3D printers, a kitchen or rooms for playing video games if you visit Oodi in Helsinki. But let’s stick to a traditional, book-filled library. Now, imagine that the owners have decided to do an experiment: the library materials are not arranged in any particular order.

Do you expect to find ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’ there? Perhaps by sheer luck or after spending hours rummaging through books. Most likely, during the process, you’ll come across another book that catches your interest instead. Or you may simply find books on statistics, law or something else that you don’t even want to open. The worst scenario: finding the book but in a language you don’t know. But well, then it’s just a matter of finding a dictionary, isn’t it? Honestly, I would call this library chaos, and I doubt many people would be interested in it. Surprisingly, though, this chaos is not uncommon in science.

Researchers generate large amounts of data, which is fundamental for testing hypotheses and building knowledge. However, when it comes to handling this data, there seems to be as many approaches to organizing it as there are researchers. This is where the problem arises: if each researcher adopts their own personal style in organizing and proceeding with their work, how can we efficiently share methodologies, reuse data and collaborate effectively? Ideally, science should be transparent and collaborative, rather than opaque and hidden.

A solution: set rules

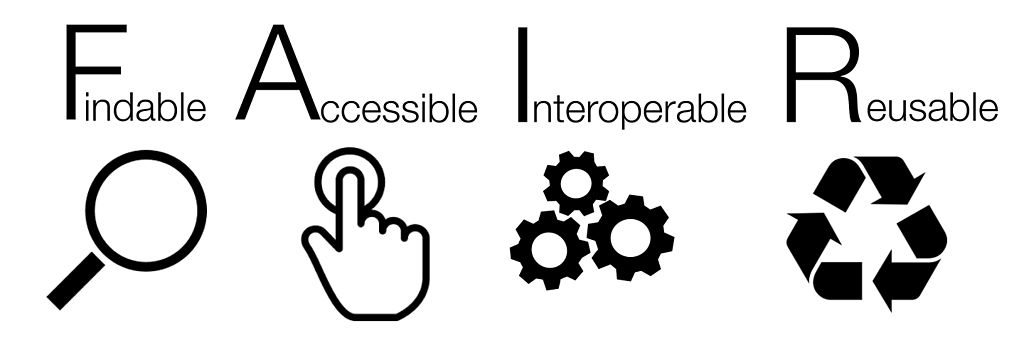

Here is where FAIRness comes into play. In 2016, a group of scientists devised guidelines for the proper integration of data into our modern digital ecosystem. These guidelines, known as ‘FAIR Data Principles’, aim for data to be:

Returning to the library, let’s see how these principles translate:

Findable: the library shelves are neatly organized with each book cataloged in a searchable database. Of course, every book has a clear title, author and subject.

Accessible: anyone can enter the library and borrow books without any barriers. No memberships, fees or restrictions of any kind.

Interoperable: the library’s cataloging system follows standardized rules and formats recognized by other libraries. So that people can easily borrow books from different libraries, request interlibrary loans, and access digital resources from online databases.

Reusable: this is already implicit in lending books, i.e. rereading them. But we could think about reuse further, by having users that write summaries, adaptations or comment on specific aspects of the books, encouraging others to read them.

That is, just 4 guidelines that can turn our chaotic library into a cozy space where one can happily spend hours and find everything needed. But note that science is not (just) about books but about data, metadata (data about data), digital resources (such as software code, algorithms, protocols, and workflows) and repositories.

Moreover, despite accessibility, FAIR doesn’t require data to be openly available. For example, patient data used in biomedical research is highly sensitive, and legislation may prohibit sharing it openly. A solution can be to anonymize the data, although this varies depending on the specific circumstances. Therefore, keep in mind that FAIR principles do not necessarily mean complete openness, although openness is encouraged whenever possible.

“To define is to limit” wrote Oscar Wilde. However, in this case the benefits of defining and following guidelines outweigh the drawbacks of data inaccessibility and lack of reproducibility. FAIR Data Principles seek structure and order in data and derivatives, thus promoting transparency, collaboration, and efficiency. That’s fair science, don’t you think?

PS: Although defining might be good sometimes, don’t ever limit yourself!

Melina Estela Dalmau works as a doctoral researcher in the Neuro-Innovation PhD programme. Her research seeks to bridge the gap between imaging and brain tissue.