Aidan Mason-Mackay: What’s a Physics Simulation?

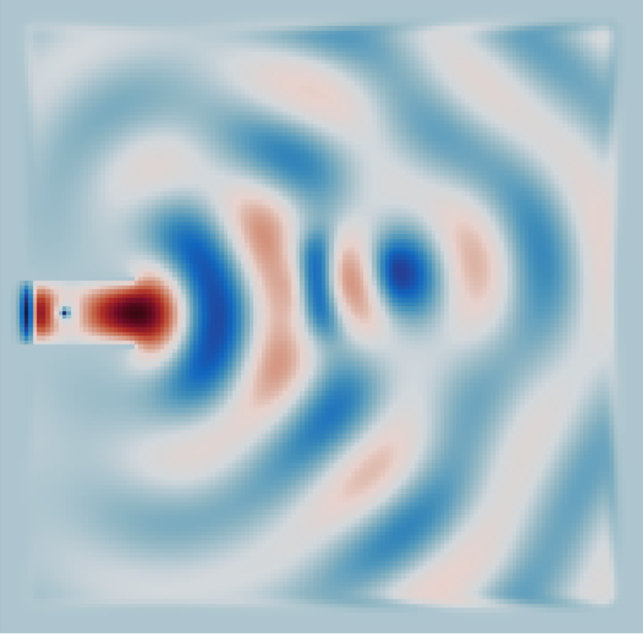

Physicists use simulations all the time to create virtual representations of things in real life. They might, for example, simulate flow over an airplane wing to predict how much lift it can generate, or simulate the forces acting on a bridge during heavy traffic, to check where its weakest points are. In video games, they simulate things like gravity, to make the game feel more life-like.

There are big companies dedicated to building huge software packages for running physics simulations, helping us investigate things like room acoustics; weather patterns; or the way chemicals are transported through our blood streams. The world is so complicated that these simulations need to leave out most of the physics that’s really involved, and the art of a good simulation is working out what physics you should and shouldn’t include.

I use simulations a lot in my research. I’m trying to make improvements to MRI image reconstruction, and simulations help me to test out how well my reconstructions are doing. I make simple simulations of the brain and simulate taking MRI measurements. Then I use this synthetic data to see if I can recreate the original image. Without access to this “ground truth”, I’d have a hard time testing if my reconstructions were any good.

The same ideas can be used in a field known as optimal design. Engineers need to make tons of design decisions as they go, aided by their intuition and physics knowledge. It’s hard to optimise designs when there are huge numbers of interplaying variables to tune. With optimal design, we first develop a simulation or “digital twin” which captures the most relevant physics. Then we build an optimisation algorithm that can tune the variables to minimise or maximise things. Maybe we want to minimise the material cost or maximise efficiency, or likely we’re looking for a happy medium between a lot of factors. An optimal design algorithm will move through the parameter space following a set of rules, until it lands on an optimal solution. Of course, the simulation is never perfect and will discount all sorts of important features. But it can be a strong guiding force to help engineers optimise and save on expensive iterations through different designs.

Multiphysics simulations are continuously improving, becoming both more complex and more efficient. Traditional modelling and optimal design techniques are also being enhanced by machine learning and AI algorithms, and they’re likely to see a huge boost if the promises of quantum computing transpire.

The field of multi-physics simulations is very interdisciplinary, requiring theoretical mathematics, engineering, high performance computing, and plenty of physics. It’s an exciting and growing area that helps us innovate faster.

Aidan Mason-Mackay works as a doctoral researcher in the Neuro-Innovation PhD programme. His research focuses on improving the time resolution of functional MRI.