Kanishka: Rhythms in Nature and Rhythms in the Brain

Have you thrown a pebble in the lake and noticed how that creates concentric rings around the center of the disturbance? Those expanding rings are called ‘ripples.’ These ripples are simple but powerful examples of how a local event can create organized patterns over space and time! Interestingly, the human brain operates in a somewhat similar way.

Some brain processes lead to physical actions – like movement and speech, while some are “hidden” and cannot be observed as such. These include processes such as thinking, mind wandering, or forming memories. Scientists study these processes by looking at their footprints in the brain through brain activity much like ripples spreading in the water. This activity can appear in different patterns – some are rhythmic (repeating over time) and some non-rhythmic. In this blog, we’ll focus on brain rhythms.

What are brain rhythms?

Brain rhythms reflect synchronous activity of a large group of neurons, which is characterized by their frequency ranges, each linked to a different brain state and functions. Frequencies tell whether the rhythm is fast or slow. The faster the rhythm, the more local in the brain it becomes. For example, slow rhythms such as delta rhythms during slow-wave (light) sleep are widespread, while fast rhythms are local.

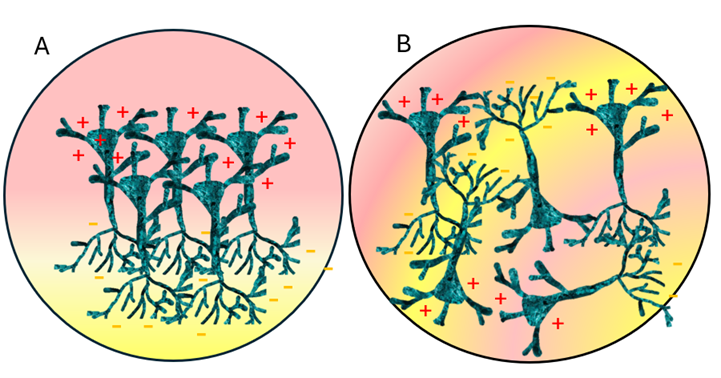

Interestingly, these rhythms are very strong in an area called “hippocampus”. This happens because all the neurons in the hippocampus are arranged in a similar manner that their electrical activity sums together, creating large local field potentials and strong rhythms. We can think of it like people rowing a boat on the lake: when everyone rows in the same direction, the boat moves efficiently, but when everyone rows randomly, progress in weak and chaotic.

Rhythms provide a time window within which the neurons can come together for some purpose. For example, duration of a gamma rhythm (30-100Hz) cycle lasts about 10-30 ms which means synchronized activity of many neurons in that time window, for a particular function. Similarly, theta rhythm (6–12 Hz) is prominent rhythm in the hippocampus, associated with movements as well as in Rapid eye movement phase of sleep. However, not all brain activity is rhythmic. Hippocampus also shows some non-rhythmical or irregular patterns.

Sharp wave and ripples

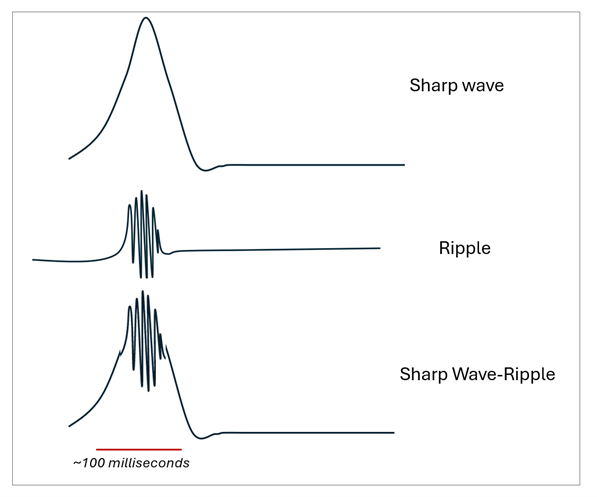

Among hippocampal activity patterns, this ripple like pattern called ‘Sharp wave ripple’ is quite fascinating. This fast pattern originates in the hippocampus and can be thought of as the lake-ripple pattern in the picture. Most often they occur riding on a sharp wave which precedes it (picture 2).

This sharp wave-ripple pattern is a very strong and short-lasting activity (occurs with hundreds of millisecond window) and very local, meaning that it is generated in a specific region in the hippocampus but the effects could be seen best from another layer (just like the ripples spreading to a distance). They are about 140 to 200 Hz frequencies in rodents and 80 -140 Hz in humans. Each sharp wave lasts roughly 50 to 100 ms.

Studying ripples are important events in memory consolidation, which is mostly happening during offline states of the body like sleep or quiet wakefulness. These are the events wherein the brain replays the recently acquired events which eventually are stored as long term memories. These events are replayed about 8 times faster than the actual events (fast oscillation, fast processing speed!). So, we can say that the sharp wave ripples are electrical signatures of memory consolidation.

Another interesting note about the sharp wave content is their resemblance to an interictal spike, which are signatures of a pathological event, called Epilepsy. This means that any abnormality in the nature of sharp waves could turn them into pathological events. In fact, both sharp waves (normal) and epileptic spikes (abnormal) originate in the hippocampus, which makes this beautiful structure a double-edged sword!

Why brain rhythms matter

In conclusion, brain rhythms are a telltale of different states. By studying rhythms like sharp-wave ripples scientists are uncovering the mechanisms behind memory consolidation and how disruptions in these rhythms may contribute to disease.

Kanishka works as a doctoral researcher in the Neuro-Innovation PhD Programme. Her research focuses on functional imaging of brain-wide networks associated with momentary events. She works in Prof. Heikki Tanila’s Neurobiology of Learning and Memory research group.