Climate tipping points and international climate law: Is law equipped for the challenge?

By Vivien Reh, Doctoral Researcher at the University of Eastern Finland

Finland, among many other countries in Europe and around the world, has seen a record-breaking heat wave for much of July 2025, surpassing previous records and feeding into a growing global acceptance that the occurrence of extreme weather events seems to have become the new norm. At the same time, global atmospheric CO2 concentrations are nowhere near a decline, with a record high in 2024 of 422,5 ppm, a 50% increase from pre-industrial levels. Such numbers make it hard to deny a correlation between increasing greenhouse gas emission levels and extreme weather events – and science would agree.

In fact, new scientific findings have emerged supporting evidence that current weather conditions are just the tip of the iceberg. Scientists are now warning of a phenomenon, so-called climate tipping points, which poses much greater, irreversible and abrupt changes in the Earth system. These threats could be more probable and their impacts more widespread than previously thought and understood.

In light of such findings the question emerges whether the current international legal framework on climate change is equipped with the necessary tools to take on and incorporate these novel scientific findings and whether the argument of scientific uncertainty will continue to remain the immovable pillar against which scientific warnings have crashed for decades.

In this blog post I share some key take-aways from the recent Global Tipping Points Conference in Exeter which convened in early July, as well as some findings from my own research on the implications of the emergence of novel science for international climate law.

What are climate tipping points and why do they matter?

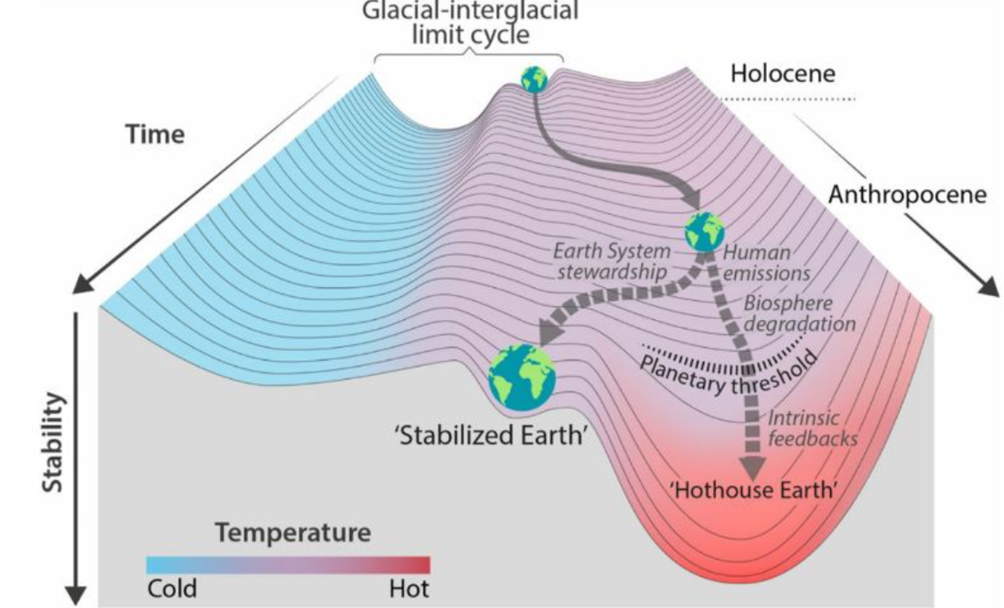

Climate tipping points are critical thresholds, mostly driven by the average global temperature increase, beyond which certain elements of the Earth system tip over into an alternate state. In more practical terms, this means that environmental, temperature-driven stresses can become so severe that certain parts of the Earth system move from their current inhabitable state into a different regime, thereby becoming un-inhabitable for the species living within them currently, including humans. This process is in most cases irreversible.

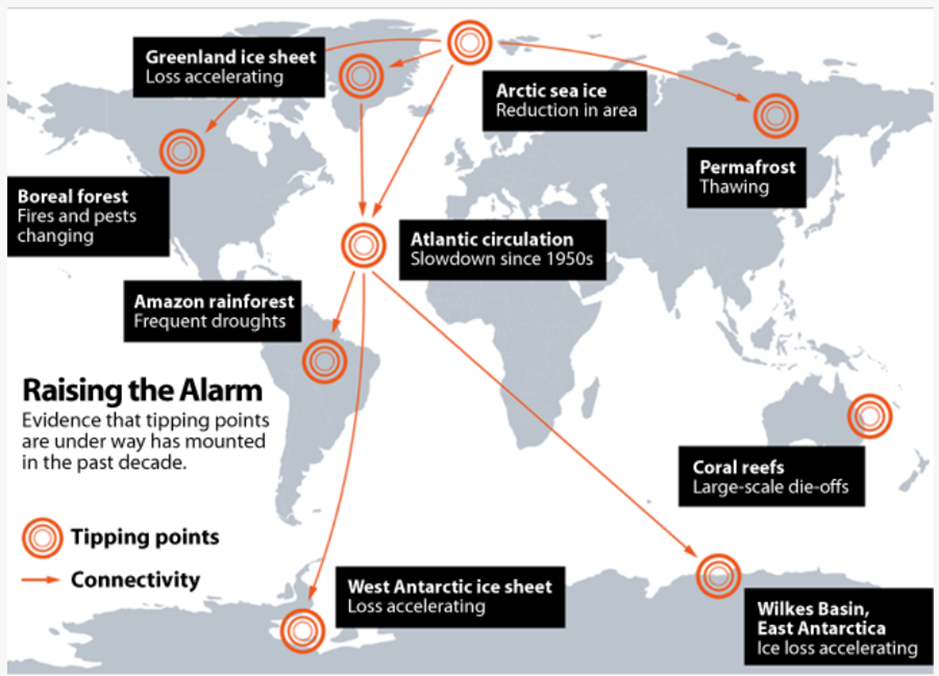

The concept of climate tipping points has been around for almost 20 years. Initial estimates regarding their occurrence, however, suggested that they could only be crossed if the global average temperature increase exceeded 5°C. Yet, contrary to that belief, the scientists at the conference emphasized that five major tipping systems have been determined to be at risk of crossing their respective tipping points already at the present level of global warming: the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets, warm-water coral reefs, North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre circulation, and permafrost regions.

These changes in the Earth system would not only be irreversible but would cause chain-reactions that could trigger the crossing of other tipping points leading to a domino effect. This would have global consequences lasting long after the actual tipping event occurred (committed impacts). The Global Tipping Points Report (2023) summarizes this: climate tipping points and concomitant regime shifts “pose threats of a magnitude never faced by humanity”.

Conference presenters reiterated on multiple occasions that these threats to humanity stem not only from significant ecological and environmental impacts but also from rapid and profound changes to societal and economic systems. For example, the tipping point associated with the slowdown or even potential shutdown of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) alone could result in never-before-seen shifts in weather patterns that threaten food security, availability of inhabitable land, and the perseverance of existing societal and economic structures, as well as cultural heritage with unequal and unjust consequences to name a few. The impacts are widespread, eroding resilience and leading to territorial and existential crises that threaten national security. As such, tipping points demonstrate that the climate crisis is far more severe in scale and impact than is commonly understood.

Therefore, as conference presenter Niko Wunderling stressed, it is vital that the temperature goal of 1.5°C is upheld, otherwise there is a high likelihood of moving into the realm of “high risk” with respect to climate tipping points. A central message that was conveyed during the Climate Tipping Points Conference is the fact that every additional tenth of a degree matters – a crucial piece of information that is often significantly underestimated by scholars and the general public alike.

Despite such clarity regarding the need for action, current global greenhouse gas emissions and action plans are well on track for a multi-decadal overshoot scenario in a 2.7°C world, further widening the gap to 1.5°C every year and increasing the likelihood of climate tipping points and a destabilized Earth system a possible reality. The Tipping Point Conference statement highlighting relevant science and warnings of future developments can be found here.

Scientific uncertainty and the challenges that come with it

Climate models have performed very well so far when tasked with predicting certain processes in the natural world. Examples include changes in global mean temperatures, the enhancement of the hydrologic cycle (dry places becoming drier and wet places becoming wetter) and rising sea levels. However, when it comes to more intricate predictions regarding changes in atmospheric composition or the thermohaline circulation of the ocean, the disparities between the individual models becomes more apparent. The main reasons for these discrepancies presented at the conference lie in natural variability, differences in forcing and differences in feedback within these models.

Such variations between climate models have contributed to general scientific uncertainty regarding climate tipping points as the currently available data makes it hard to predict when or where climate tipping points may occur and how they might interact with each other. The sheer scale of many of these global tipping points and their interconnected nature, spanning all the way from the local to the global level, increases the uncertainty regarding their drivers, interplays and concrete impacts (immediate and long-term).

Moreover, keynote speakers at the conference revealed that depending on the rate of climate change, a slowed-down pace could still lead to tipping events. But rather than an abrupt collapse, systems may re-organise and a sudden change may never occur. That is not to say that such a scenario would eliminate the possibility of cascading effects and the triggering of other tipping points.

Such overall uncertainty regarding time scale, location and impact has fostered the assumption by politicians, economists and even some natural scientists that climate tipping points are of low probability and little understood.

However, scientific uncertainty should not be confused with scientific unreliability, meaning that an event that is associated with low probability due to insufficient available data can still constitute a high-impact and therefore high-risk event. Scientists warn that despite the deep scientific uncertainty the risk of climate tipping points occurring is very real and very serious and should be handled accordingly.

Tipping point science and implications for international climate law

Risk can be assessed via the following formula: Risk = Probability x Impact. As such one can reasonably conclude that a low-probability, high-impact event can still amount to a substantial amount of risk despite its low probability.

Firstly, this implies that climate tipping points do in fact constitute global catastrophic risks due to the immense impacts they constitute. Accordingly the prevention of climate tipping points falls squarely within the scope of both the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Paris Agreement, as tipping points are ultimately the result of “dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system” from increasing greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere (UNFCCC), and are therefore part of the threats constituted by climate change (Paris Agreement).

Secondly, such a risk assessment obliterates the argument in favour of using scientific uncertainty and low probability of certain events as reasons for inaction. This is reflected in the Advisory Opinion of the International Court of Justice that was issued in July 2025, in which the court reaffirms in Paragraph 293 that states are under an obligation to take actions of prevention against climate change despite existing scientific uncertainty.

Moreover, in the same paragraph the court states that scientific findings on the probability and seriousness of possible harm informs the required standard of due diligence. This implies that states are required to keep up with the latest science in order to adjust their due diligence standards accordingly. In her talk at the Tipping Point Conference Violetta Ritz argued that such due diligence obligations are equivalent to prevention obligations. She contended further, in line with the findings of the court (ICJ Advisory Opinion para. 293), that such obligations must be upheld despite the existence of scientific uncertainty. Given the vast amount of data available already and the immense impacts linked to the occurrence of tipping points, the scientific finding that ‘the higher the emissions, the more likely it is for climate tipping points to occur’ must be accepted as a fact. Thereby states would be rendered unable to interpret the Paris temperature goal and specify their climate targets to their liking. However, such observations are not yet reflected in real-life implementations, as the progression of due diligence standards rarely aligns with the highest possible ambition.

As such it was further argued during the conference session on the “Limits of International Environmental Law” that the legal obligations set out by the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement must be interpreted under the consideration of principles of international environmental law. Here, too, the ICJ Advisory Opinion provides an answer by stating that, indeed, obligations of states in respect of climate change must be considered within the relevant and applicable law, including certain guiding principles, such as the principles of sustainable development, common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, equity, intergenerational equity, and precaution.

This clarification by the court is much needed, as presenters at the conference such as Karen Morrow highlighted that many of these principles, in particular the principles of precaution and prevention do not currently fulfil their purpose in the way they are being interpreted and applied. Given the mismatch between state obligations to apply such principles to guide their climate actions and the prevalent inconsistencies in the principles’ application, she suggested that, going forward, these principles need to be interpreted in their literal sense: prevention and precaution.

Looking back at the aforementioned prevalent gap between the evident need for climate action and the all-time high greenhouse gas emission levels, the ICJ Advisory Opinion seems to have arrived at the right point in time. It reinforces the scientific understanding of climate change as an ‘urgent and existential’ threat (ICJ Advisory Opinion para. 73), and shines the spotlight on the importance of an immediate fossil fuel phase out, which, alongside a halt to deforestation, is the only method of prevention for many climate tipping points. Reaching net zero would lead to a halt of global warming within the upcoming years, thereby limiting the risks of a potential overshoot scenario significantly.

The relationship between science and law has been historically marred by obstacles and barriers to interaction. Complicated scientific language, inaccessibility of the legal playing field, political undercurrents, differing time scales, and of course the omnipresence of scientific uncertainty are all factors that can hinder the exchange between the two disciplines. This is all the more true in the context of climate tipping points, a field so heavily reliant on science and the transmission thereof into the law-making process. As such, it is crucial to forge and flesh-out pathways that enable scientists and lawmakers to engage in meaningful dialogue and further the understanding between the two disciplines.

Forums such as the Tipping Point Conference in Exeter, as well as the upcoming climate COP30 in Belém are relevant institutions to foster such exchange. These fora serve as points of interaction to build momentum, improve governance structures, including the involvement of relevant institutions, and increase the precision of risk communication.

For more information on the Global Tipping Points Conference and highlights regarding positive tipping points, positive movements in society that counter negative tipping point impacts, Carbon Brief provides a full report on all topics discussed.