The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – fit for the next assessment cycle?

By Moritz Petersmann, PhD Candidate working on project: Fit for governing the triple planetary emergency? Towards enabling sustainability transformations at international science-policy interfaces

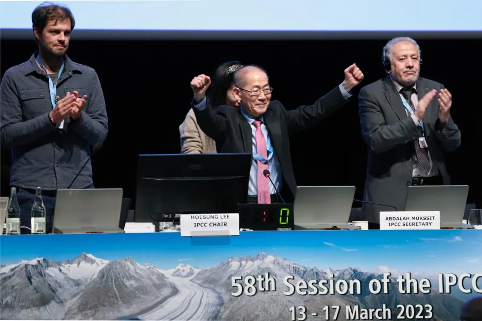

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published the Synthesis Report and its Summary for Policymakers (SPM) for the sixth assessment cycle after a marathon week of deliberations during its 58th session, held in Interlaken from 13th-19th March 2023. The IPCC is now transitioning to a new assessment cycle, and in this context it is relevant to ask if it is the time to re-think the IPCC model? The blog post shares personal observations from the Interlaken meeting, reflecting on the inclusivity of the IPCC process and the suitability of the IPCC model for a science-policy interface in a changing political context. I participated in the meeting as a Writer for the Earth Negotiations Bulletin, which issued a detailed summary and analysis report.

The Synthesis Report does not contain new scientific findings but condenses the state of scientific knowledge on climate change, including its physical base, impacts and mitigation options. As other IPCC reports, the Synthesis Report is prepared by appointed authors, undergoes several review steps, and is finally endorsed by IPCC member states. Approval of the high-level SPM requires consensus of all participating IPCC member states on each paragraph, figure, caption, and footnote of the document. This painstaking process culminated in around-the-clock deliberations on Friday, 17th March until concluding on Sunday evening, two full days after the scheduled closure of the meeting. This seriously impaired the inclusivity of the process, as many delegates had been unable to extend their travel in order to participate in the approval process.

The IPCC looks back at eight productive years, which culminated in the approval of the Synthesis Report. The Synthesis Report integrates findings from three IPCC Working Group (WG) assessments and three special reports, including the “1.5 degree report”. Being entirely based on these previous IPCC publications, the main messages conveyed by the Synthesis Report are not new: Human activities have “unequivocally caused global warming” of 1.1°C. Climate change has adverse impacts and causes losses to nature and people, that escalate with “every increment of global warming”. While “deep, rapid and sustained” emission reductions are necessary, mitigation policies fall short leading to a projected global warming of 3.2°C by 2100. There are however multiple opportunities for scaling up climate action. The window for opportunity is narrow with the level of greenhouse gas emission reductions occurring in this decade being decisive, “whether warming can be limited to 1.5°C or 2°C”.

Approving the SPM of the Synthesis Report means that IPCC member states negotiate which messages are most crucial for policymakers. Basis for the deliberations is a final draft report, which undergoes several review steps ahead of the meeting. In the process, IPCC Authors act as “penholders”, tasked to ensure scientific robustness of the report, while addressing requests of delegates. Accredited observer organizations have the right to participate and, if given the opportunity to speak, their statements gain significance with support from like-minded member states. Canada, for example, supported the Inuit Circumpolar Council in their suggestion for stronger inclusion of indigenous knowledge in IPCC assessments.

The approval process in Interlaken, once again, illuminated the diverging interests and priorities of participating countries. On the relevance of different mitigation options for example, Saudi Arabia actively advocated stronger emphasis on the role of carbon capture and storage, and carbon dioxide removal technologies. Delegates from Denmark, Norway and Germany suggested highlighting the central role of renewable energy technologies. Another reoccurring stumbling block was attribution of responsibilities for historical emissions: While India and other developing countries requested including more specific information on developed countries’ emissions, this request was opposed by the US.

Perhaps the most significant observation from the approval process in Interlaken was the lack of inclusivity in the late hours of the week. Approving the SPM line by line took much more time than initially scheduled for the meeting. On Thursday, delegates worked until 2.00 am and continued deliberating around the clock from Friday morning until finalizing their work on Sunday evening, two full days after the scheduled closure of the meeting. Such working mode was especially challenging for small delegations, and frustration about the pace of approving text became increasingly apparent during the weekend. Many delegations, especially from developing countries, had to leave before the closure of the meeting and member states’ representation in the room was obviously imbalanced. Several member states expressed their concern about the inclusivity of the process. On Saturday night, one delegate declared on the lack of inclusivity in an emotional statement: “The ones struggling the most are the ones that are leaving…it is our lives that we are here fighting for!”

Developing country participation both in report preparation and government plenary meetings has been long debated in the IPCC. Undoubtedly, progress has been achieved since the first IPCC Chair Bert Bolin noted in early years of the IPCC: “Right now, many countries, especially developing countries, simply do not trust assessments in which their scientists and policymakers have not participated. Don’t you think global credibility demands global representation?” Establishing a Trust Fund in the 1990s to financially support participation of one delegate from each developing country had a positive effect on developing country presence. Considering that stakes in the political debate on climate change are rising, increased efforts from the IPCC are required to tackle asymmetries in member states’ capacities. This is especially important for key moments in the IPCC process such as the SPM approval. A seemingly straightforward suggestion made by several delegations in Interlaken is to “plan for longer meetings or fund the participation of a second delegate from developing countries.”

Other dimensions of inclusivity, and the lack thereof, have been frequently discussed ever since the inception of the IPCC. These discussions revolve around diagnosed disciplinary, gender and geographical biases and a lack of epistemic diversity (for example limited inclusion of indigenous knowledge) in the production of assessment reports. The IPCC commits itself to ensure that authors contributing to assessment reports reflect a “range of scientific, technical and socio-economic views and backgrounds” as well as “a balance of men and women”. Looking at the sixth assessment cycle, a trend towards more diverse author groups is noticeable, especially considering the extremely low baseline occurring from assessment cycles in the 1990s. However, asymmetries clearly persist: Overall, the share of authors from developing countries contributing to WG assessment reports was approximately 35%. Out of 234/270/278 WG authors 28/41/29% were women and 72/59/71% men (WG I/ WG II/ WG III). Social scientists continue to be clearly underrepresented. Furthermore, the IPCC struggles to incorporate indigenous knowledge in its assessment process, even though its relevance for creating solutions and tackling climate change is one of the findings of WG II. Addressing all dimensions of inclusivity continues to be central for strengthening the legitimacy, relevance and credibility of the IPCC process and its outputs.

Besides finetuning the IPCC through important procedural improvements, a changing international governance context challenges the IPCC model. The adoption of the Paris Agreement marks a turn towards a polycentric governance architecture, in which implementation of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) determine the success towards the global goal of keeping the global average temperature increase well below 2°C, preferably limiting it to 1.5°C, above pre-industrial levels. In the context of implementing the Paris Agreement, the IPCC needs to address (at least) three questions for maintaining its relevance for national and international policymaking:

1. How does the IPCC transition from producing scientific evaluations to solution-oriented assessments?

2. How can the IPCC support climate action on national, regional, and local levels?

3. How does the IPCC feed in the Global Stocktake carried out under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change?

In 2015, the newly elected Chair Hoesung Lee declared that he “would like to be remembered as the chairman that shifted the IPCC’s focus to solutions”. Concluding the sixth assessment cycle eight years later, it is debatable if the IPCC has successfully shifted towards solution-oriented assessments. Arguably, the request for the 1.5 degree report by the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change offered the opportunity for such a shift since the IPCC was invited to compare the effects of temperature increases of 1.5°C and 2°C and describe possible ways to achieve these goals. While the IPCC noticed that limiting global warming to 1.5°C would require substantial societal and technological transformations, the 1.5 degree report failed to assess the feasibility and viability of possible pathways for these transformations. This failure could be overcome by addressing socio-economic aspects of societal transformations, which calls for stronger inclusion of social scientists in the production of future IPCC reports. A turn towards solution-orientation requires the IPCC to engage in a reflective process on its self-image of providing policy-relevant knowledge without being policy-prescriptive.

Induced by the Paris Agreement, it is mainly national policymaking that requires (solution-oriented) knowledge on climate change and possible adaptation and mitigation pathways. Shifting its understanding from being policy-relevance mainly for the global policy sphere under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, towards national, regional and local levels, requires re-imagining the IPCC model. The IPCC’s current focus on producing global knowledge offers little action-oriented guidance for policymakers on sub-global entities. Admittedly, re-structuring the IPCC for making it fit for purpose to support polycentric climate action constitutes a tricky challenge, but the ways forward are worth exploring.

With the Global Stocktake process under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, the IPCC has a clear perspective of maintaining its policy-relevance on the global level. Every fifth year, the Global Stocktake reviews collective progress towards achieving the goals enshrined in the Paris Agreement. The Global Stocktake intends to inform subsequent rounds of NDCs and encourages scaled up ambition to bring climate action in line with global objectives. Results from the IPCC’s sixth assessment cycle, recently synthesized in the Synthesis Report, provide key input for the first Global Stocktake, which will be completed later this year. Looking ahead, a critical question is how IPCC outputs from the next assessment cycle will feed into the second Global Stocktake, which is scheduled for 2028. With IPCC assessment cycles lasting 7-8 years, there is the risk that the IPCC loses its policy-relevance for this crucial instrument under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. This challenge will need to be addressed at the start of the 7th assessment cycle, which kicks-off just after new members for the IPCC Bureau and Task Force Bureau are elected at the 59th session, 23rd -27th July 2023.

The IPCC plays an influential role as the central science-policy interface of the climate change regime. Its mode of operation arguably determines its legitimacy, relevance, and credibility. In a changing political context, induced by the Paris Agreement, the IPCC is challenged to deal with questions about its structure and working mode.

For consistency with IPCC language, this blog post uses the term “developing country” instead of “Global South”.